Growing gray areas

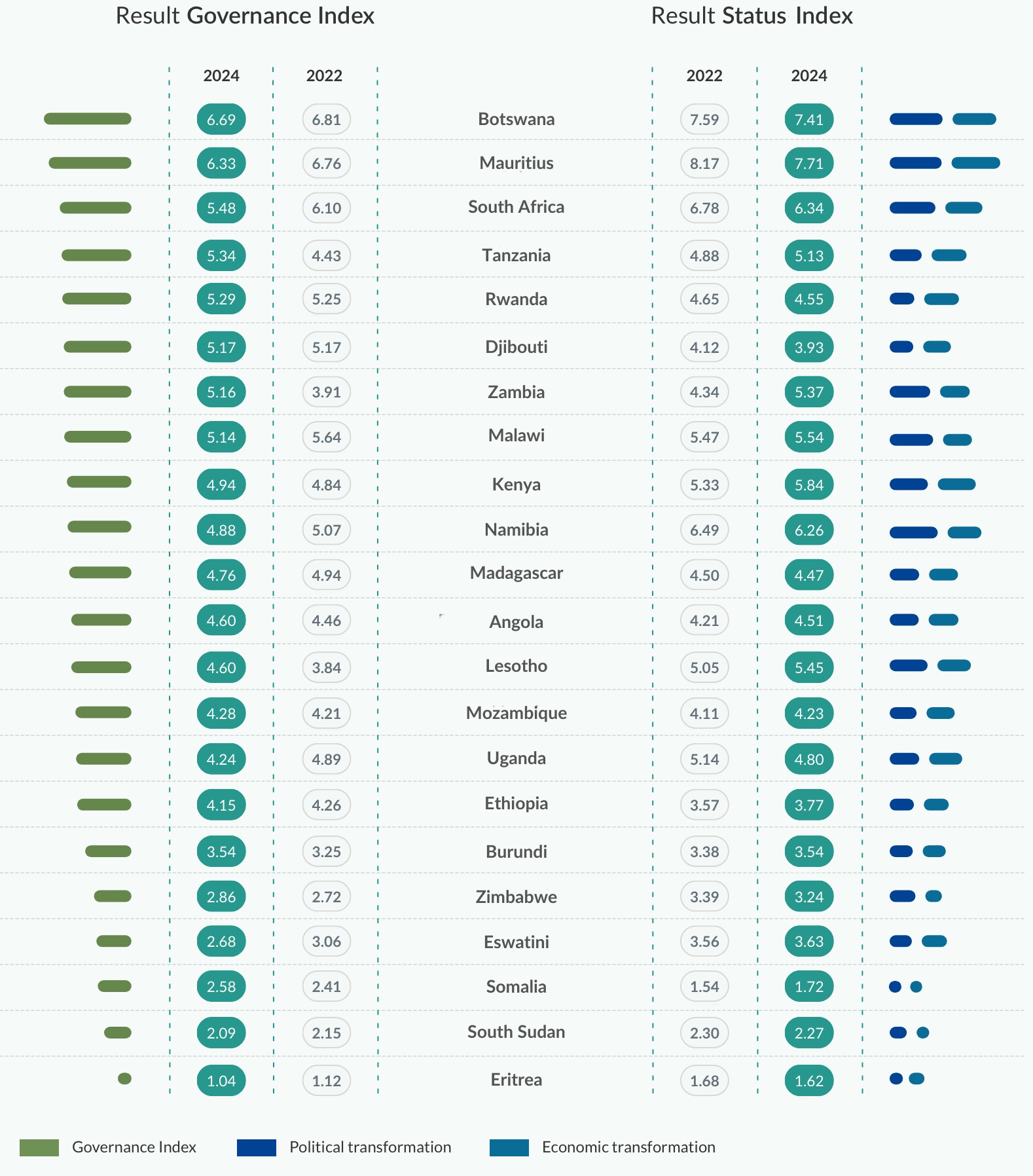

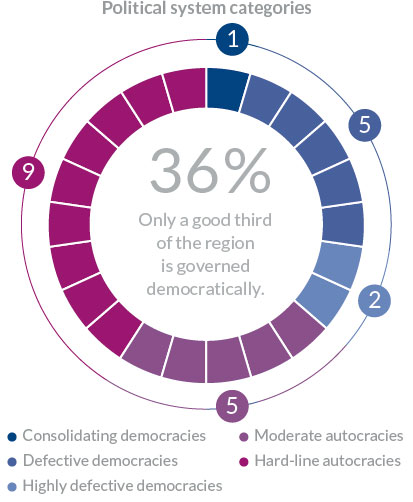

The return of Kenya and Zambia to the realm of democracies is a beacon of hope in the region. However, both countries still lag significantly behind the level of political transformation they had achieved a decade ago. This pattern holds true for most other democracies in the region, some of which have suffered major setbacks. The gray area of unconsolidated democracies is growing. The quality of governance in most countries ranges from moderate to weak, as governments struggle with lingering economic woes and formidable structural obstacles.

Three trends are shaping the course of political transformation in Southern and Eastern Africa. First, democracies that have witnessed no leadership turnover since gaining independence are becoming increasingly susceptible to corruption and intra-party patronage dynamics. This, in turn, has eroded public satisfaction with democracy, a phenomenon evident in Botswana, Namibia and, most notably, South Africa. Second, Kenya (+0.93 points) and Zambia (+1.60 points), have displayed remarkable democratic resilience, largely owing to the vigor of civil society. In both countries, a coherent and programmatically clear opposition fought a successful election campaign that culminated in a return to democratic governance, albeit with lingering fragility. Third, most autocratic regimes are showing signs of a hardened crackdown on dissent. Only Tanzania is moving in the opposite direction, embracing liberalization. On average, the region’s 14 autocracies have seen their largest declines in the freedoms of assembly and association (-0.37) and judicial independence (-0.61). Zimbabwe has been downgraded from a moderate to a hard-line autocracy.

The level of socioeconomic development in the region has dipped by 0.14 points since the BTI 2022. While the impact of external shocks has been less severe than anticipated, it has nevertheless contributed to a challenging overall situation, especially in terms of poverty alleviation. Many governments have set vague, difficult-to-operationalize goals, often stumbling in their execution. Structural problems and conflicts have made governing even more difficult. The civil war in Ethiopia momentarily subsided with a cease-fire in late 2022, but the conditions for enduring peace remain precarious due to regional instability in the Horn of Africa. Conflict is growing in neighboring Somalia, and South Sudan remains in a fragile state.

Political transformation

Oppositions are adopting new strategies

The importance of elections and voter-mobilization strategies for the development of democracy is underscored by the examples of Kenya and Zambia. In Zambia, mounting discontent since 2019 has provided the groundwork for Hakainde Hichilema and the United Party of National Development (UPND) to secure victory over Edgar Lungu and his Patriotic Front. Three other factors have played a key role in this transition. First, the country’s traditionally robust civil society proved essential to promoting democracy by advocating for fairness and transparency in the electoral process. Second, the UPND managed to expand its voter base beyond its core supporters and positioned itself as an effective alternative. Third, the defeated candidate, Lungu, accepted the election results. Although challenges persist in areas such as the separation of powers and judicial independence, Zambia’s peaceful transfer of power sends a positive signal in the region.

Similarly, the narrow victory of William Ruto in Kenya in 2022 has been attributed to a shift in the rhetoric used to mobilize voters. Presenting himself as an outsider in a system dominated by political dynasties and ethnic loyalties, Ruto centered his campaign on class-based identities and promised economic reforms. And while the loser, Raila Odinga, attempted to challenge the results, this did not lead to violent unrest.

Negative trends are evident in South Africa (-0.70 points) and Mauritius (-0.60). South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), grapples with patronage networks and factional disputes, which President Cyril Ramaphosa struggles to contain. Many of the country’s political institutions, especially at the local level, are underfunded, weak and prone to corruption. While many South Africans are dissatisfied, they do not see a viable alternative among the current range of oppositional parties. This positions South Africa, with a political transformation score of only 7.00 points, closer to the gray zone of vulnerable, defective democracies like Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi and Zambia, even though its legal institutions remain robust.

Similar to South Africa, Mauritius has long been considered a stable democracy. However, during the period under review, the ruling party has expanded its power, as evidenced by media censorship and self-censorship. In addition, parliamentary oversight of the executive branch has weakened. In Namibia, although the opposition now has more members in parliament than it did in 2020, it wields little influence.

Not much has changed in terms of political transformation among the region’s autocracies. Elections in Angola, Djibouti and Uganda unsurprisingly confirmed their respective ruler’s grip on power. Progress has been recorded in Tanzania, though it remains unclear whether President Samia Suluhu Hassan, the successor to the late John Magufuli, will introduce further reforms.

In failing states like Somalia and South Sudan, virtually all prerequisites for a functioning state are absent, including a monopoly on the use of force and basic infrastructure, such as water, electricity and health care services. A substantial portion of Somali territory is controlled by al-Shabaab and other militias, with the regions of Somaliland and Puntland existing as secessionist, not internationally recognized states. Conflicts between the central government and the federal states have hindered plans for administrative and tax-collection reforms. Efforts to transition from clan-based to universal suffrage have also proved unsuccessful. In South Sudan, there have been no elections since the country gained its independence in 2010, with President Salva Kiir often ruling by decree. Political institutions, such as the parliament, are mere façades, and the public continues to suffer under a dire civil and human rights situation.

Economic transformation

After the pandemic comes inflation

Although nearly every economy in the region has recovered from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, two countries have shown exceptional growth in 2021: Botswana, which achieved an 11.4% increase in GDP, and Rwanda, which saw growth of 10.9%. At the same time, significant economic challenges persist, as many countries are now contending with mounting inflation worries that are primarily fueled by surging food and energy prices. The situation is particularly dire in Zimbabwe, where inflation soared to 104.7% in 2022, which was the highest rate in the world, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

In Kenya, Zambia and Tanzania, the political landscape has become more conducive to economic transformation. Kenya’s peaceful 2022 elections laid the foundation for achieving the new government’s long-term goals, which include debt reduction, fortifying the private sector, and addressing the impacts of climate change. Zambia made improvements in six indicators compared to the BTI 2022, including those assessing private-enterprise efforts and a viable banking system. Tanzania saw an even greater boost to private sector growth, thanks to President Suluhu’s market-oriented approach. In fact, Tanzania made strides in all indicators related to market and competition policies, as well as the private sector.

Namibia, on the other hand, is witnessing a surge in legal and regulatory uncertainties concerning private investments, despite the removal of the initially proposed equity clause stipulating that 25% of ownership be with members of previously disadvantaged population groups under the New Equitable Economic Empowerment Framework. Other reforms, such as tax reforms, are progressing slowly or inconsistently (-0.25).

Economic transformation in South Africa (-0.18) remains disappointing. Mismanaged state-owned enterprises, such as Eskom (energy) and Transnet (rail freight), are straining the budget, and despite the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) Act, significant inequality persists. High bureaucratic hurdles imposed by the B-BBEE and the limited number of beneficiaries are also the subject of much criticism. South Africa’s weak economic performance has created spending constraints that hinder much-needed infrastructure initiatives. South Africa and Namibia, both of which fell 10 places in the inequality-adjusted Human Development Index for 2021/22, continue to feature particularly unequal income distributions.

Equally notable are the disparities observed between individual countries across the region. In many countries, a large percentage of the population still relies on agriculture, making them vulnerable to fluctuating prices for agricultural products. The informal sector remains substantial, accounting for over 90% of employment in Burundi, Madagascar, Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda, according to recent estimates by the International Labour Organization. In Madagascar, one of the world’s poorest countries, poverty increased from 77.4% in 2020 to 81% in 2022.

The countries facing the greatest challenges are those grappling with several crises at once. Somalia has been without a functioning state apparatus for over 30 years and remains dependent on imported goods. In Eritrea, the ongoing militarization of society compels the majority of the adult population to work for a pittance in national service or as soldiers, distorting the labor market and perpetuating the mass exodus of the young and educated.

Governance

The decline of a normative power

Amid the region’s enormous structural challenges, we see a worrying trend with regard to the indicators assessing a government’s ability to set priorities and implement policies. The disconnect between ambitious goals and often ineffective execution can be attributed to various factors. These encompass an underpaid, unmotivated or unprofessional administrative staff, which is particularly prevalent at lower levels of government. Additionally, a top-down management culture within state administration structures, characterized by extensive centralized decision-making, exacerbates the issue. Other contributing elements include unclear role delineation for specific tasks, insufficient resources for implementation, and challenges related to corruption and nepotism.

South Africa, showing a notable decline in the Governance Index (-0.62), serves as an illustrative example of this trend. For instance, in 2012, the government launched the National Development Plan, aiming to eradicate poverty by 2030. However, poverty has actually increased during the period under review. Similarly, unemployment surged to 29.8% in 2022. The fact that the ruling ANC and the state apparatus are heavily intertwined is a key factor behind the difficulties observed with policy execution. Corruption and mismanagement are pervasive, and state institutions have become arenas for intra-party power struggles. South Africa, once celebrated as a principled global actor, has suffered a setback in its international reputation, owing in part to its abstention from endorsing UN resolutions denouncing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This is also true of Namibia, which continues to deepen its ties to China and Russia.

In addition to the region’s traditional structural constraints, the effects of climate change are increasingly evident. While most of the region’s governments set climate-protection targets, these are often overshadowed by other political priorities, particularly with regard to economic growth. Kenya stands out as a positive exception, with over 90% of its electricity being generated from geothermal, solar and biogas sources as well as sugar processing. The country is thus making significant strides toward its commitment to achieving 100% clean energy by 2030. In contrast, Tanzania and Uganda are prioritizing economic considerations over environmental protection with their plans to construct a pipeline from western Uganda’s oil fields to the port of Tanga. Namibia’s granting of licenses for oil and gas field exploration and uranium mining between 2020 and 2022, which led to jurisdictional conflicts between the ministries responsible for each area, indicates a weak commitment to climate-friendly policies.

The Horn of Africa states are also grappling with violent conflicts. In Somalia, the most significant challenges include combating the al-Shabaab insurgency, recurring environmental disasters (especially droughts) and humanitarian crises. In South Sudan, numerous inter-communal conflicts have the potential to escalate into larger conflicts. In Ethiopia, the strong politicization of ethnicity within a system of “ethnic federalism” underlies an internal conflict that displaced over 5.1 million people within the country in 2021.

Outlook

A key factor in addressing the region’s complex problems remains the legitimacy of governments. The examples of Kenya and Zambia underscore the close relationship between political and economic transformations. They also highlight another crucial point: the high demand for a strategically positioned opposition. Even in relatively stable democracies, there is a risk of declining political participation and waning support for democracy – not because democracy as a form of government is undesirable, but because doubts about a government’s ability to solve problems persist. Consequently, not only should there be stronger collaboration among opposition groups, but all parties must engage in more coherent policy formulation.

In terms of economic policy, conditions for businesses across the region need improvement. In particular, we need to see greater transparency in policymaking and stepped-up efforts to battle corruption. However, inflation and rising government debt are complicating reform efforts. Many countries are facing a shortage of qualified labor, necessitating an expansion of the education system. Prioritizing economic diversification is crucial, especially as some resource-extraction projects clash with climate-protection goals.

In the region’s weakest states, ensuring security remains paramount. The cease-fire in Ethiopia marks a crucial first step toward resolving the country’s violent conflict. In Somalia and South Sudan, building peace and security will undoubtedly require a much longer investment.