Governance adrift

For years, the course of transformation in many Latin American and Caribbean nations has been adrift, devoid of a clear direction. Lacking a basic consensus on how to move forward, many countries have failed to address institutional weaknesses in their economies, and polarizing political styles have become commonplace. However, amid these challenges, there are still noteworthy success stories, with the BTI 2024 showing some democratic comebacks.

The question of where Latin America and the Caribbean should be headed seems more uncertain than ever, especially in the wake of two more years dominated by conflicting developments and a lack of visionary leadership. Just as the region was grappling with the setbacks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit the area hardest on a global scale, it faced another shock with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The war has brought imported inflation and required corrective monetary policy measures that have further hindered the recovery process. At the same time, many countries in the region have continued to struggle with unresolved domestic issues.

Overall, the BTI paints a consistent picture of decline across all three dimensions of transformation in the region. In the medium term, there is a noticeable trend toward political instability or erosion of democracy, stagnating or regressing economic transformation, and, particularly since the BTI 2018, a deterioration in governance. During the period under review, the negative governance trend was linked to the personalized leadership styles of populist figures, such as Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) in Mexico, and the unconventional “cool dictator” Nayib Bukele in El Salvador. Although Bukele is primarily responsible for the region’s most significant downturns in terms of democracy and governance, with each declining by nearly 1.5 points on the BTI’s 10-point scale, he continues to enjoy high approval ratings among El Salvadorans. Consequently, his example could potentially be adopted by others in the region.

Political transformation

Heterogeneous dynamics

The case of El Salvador represents one of the most striking trajectories in political transformation observed in recent years. Delivering an effective response to the pandemic, President Bukele secured a two-thirds majority in the legislature for his party, Nuevas Ideas, in 2021, which opened the door to executive dominance. His first move was to replace all five judges of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court and the attorney general with loyalists. Shortly after assuming office, the court’s new judges ruled in favor of Bukele’s eligibility for reelection in 2024, which is in violation of the constitution. In addition, a state of emergency was declared to combat gang violence, resulting in the detention of over 60,000 suspects by the end of 2022, including thousands who, according to human rights organizations, have been unjustly incarcerated.

In Argentina, Brazil and Mexico, efforts to weaken judicial independence have proved less successful. Most recently, in late June 2023, Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court barred Jair Bolsonaro from holding public office until 2030, following his conviction for abusing power in the run-up to the 2022 presidential elections and making unsubstantiated claims of election fraud. In the same month, Mexico’s Supreme Court dealt a blow to AMLO’s political agenda by overturning parts of the contentious electoral reform package known as “Plan B,” which aimed to restructure the National Electoral Institute. In addition, the court invalidated the transfer of the National Guard to the army in April of the same year. Argentina’s Supreme Court has also taken a stance against overtly political power plays.

A distinctly different trend can be seen in the extreme polarization of the executive and legislative branches. This poses a threat to democracy, as illustrated by the example of Peru (-0.50 points). Immediately after his election victory, President Pedro Castillo faced vehement opposition from the defeated right-wing faction led by Keiko Fujimori. Congress constantly employed obstructive tactics against Castillo's government, which, for its part, struggled without a clear governance strategy and became entangled in corruption scandals. Faced with a third impeachment motion that had little chance of success, Castillo attempted a “self-coup” on December 7, 2022, in a bid to extend his power. However, the coup failed due to broad resistance from Congress, the judiciary and the military, leading to charges of rebellion and conspiracy against Castillo. The ensuing protests, some of which turned violent, coupled with police crackdowns, led to an estimated 60 deaths.

Notably, the resilience of defective democracies was also evident, particularly in Honduras (+0.33) and the Dominican Republic (+0.40). Dominican President Luis Abinader based his appointments for high-ranking positions on professional merit rather than party affiliation, aiming to enhance government transparency while protecting the judiciary from further politicization. Honduras, which had descended into autocracy under President Juan Orlando Hernández in 2017, managed to return to democracy through free and fair elections, although the outcome remains mixed. For instance, the new president, Xiomara Castro, abolished the “Secrecy Law,” which had allowed officials to conceal corrupt activities. However, she also enacted an amnesty law that could protect influential members of her party from prosecution for abuse of office. At the end of 2022, she declared a partial state of emergency to combat widespread violence – a measure that did, however, garner broad public support.

Economic transformation

Negative stagnation

Economically, the period under review was characterized by two overlapping phases. The year 2021 was marked by a phase of recovery from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was observed in most countries, though not to the same extent as in Panama and Peru. Panama’s GDP per capita surged by 13.8% after a steep decline of 19.1% in 2020, while Peru’s GDP per capita rebounded by 12% following a 12.2% contraction. However, as early as 2021, inflationary trends began to emerge in several of the region’s countries and were further exacerbated by Russia’s war against Ukraine. Of particular concern were the rising costs of energy and food, both potential catalysts for social unrest, which imposed heavy burdens on nearly all countries. Very few countries managed to meet the inflation targets set by their central banks.

Despite these challenging conditions, most of the region’s central banks remained steadfast in fulfilling their primary mandate of targeting monetary stability and began to raise interest rates. However, the flip side of this strategy was a significant slowdown in economic growth in 2022, resulting in a challenging environment, especially for lower-income populations and the overall social fabric of a country, due to reduced employment opportunities and real wage losses driven by inflation. Reflecting on the past decade, we can discern a troubling trend of “negative stagnation” in terms of socioeconomic development levels. For instance, Brazil’s Human Development Index (HDI) value now mirrors that of 2014, Mexico’s is roughly on par with that of 2012, and even Cuba, once commended for its social safety nets, has fallen below its 2011 value.

The situation regarding poverty across the region is disheartening. According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), more people are struggling with poverty or extreme poverty than before the pandemic. For ECLAC, this represents a setback of 25 years, along with a 22-year setback in unemployment that is affecting women in particular. ECLAC has also identified a “silent education crisis” as a consequence of the pandemic that has left a half of a generation of students behind.

The longer-term trend in economic transformation since the BTI 2010 – which marked the previous peak in the regional average – shows a declining score over the past decade. Exacerbated by the effects of the pandemic, this decline has been somewhat mitigated in only a few countries during the review period. Among the notable casualties of this trend are the regional “powerhouses”: Brazil (-1.29), Mexico (-1.14) and Argentina (-1.11). They belong to the region’s group of middle-income countries, all of which suffer from institutional weaknesses. In contrast to more successful nations, such as Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay – countries that have set the standard for what is achievable in Latin America – Brazil, Mexico and Argentina are particularly deficient in the areas of market organization, private property safeguards, welfare state infrastructures, environmental conservation and educational reform.

Governance

Insurmountable hurdles?

However, determined efforts to address these issues are encountering substantial challenges in governance. Observers lament the eroding or, in some cases, obstructed consensus on the twin goals of reform, which is often exacerbated by structural factors and powerful veto groups both within and outside the political system. The prospect of achieving democratically legitimized and organized change in Latin America and the Caribbean appears to be encountering formidable obstacles, a reality increasingly felt by many populations across the region, assuming they support such change at all. Many have largely adapted to the status quo, at best expecting their governments to improve their material well-being, a feat not to be underestimated.

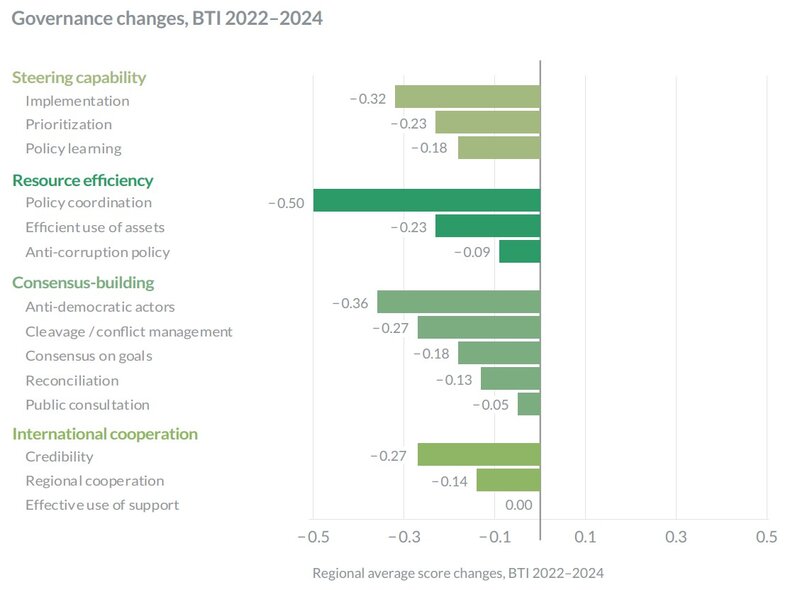

In general, the scores for most governance criteria and indicators have declined during the period under review, particularly in the areas of policy coordination (-0.50), prioritization (-0.23), implementation (-0.32), the exclusion of anti-democratic actors (-0.36), and conflict management (-0.27). This points to a perilous combination of weak governance capacity and governments’ failure to effectively manage the divisions and conflicts within their populations.

Once again, two democracies – Argentina (-0.81) and Brazil under Bolsonaro (-0.63) – are key contributors to this decline. Though Brazil traditionally boasts a well-structured public administration, a slew of often arbitrary reshufflings, job and budget reductions, and appointments of ideological sympathizers have severely hampered the efficient utilization of available resources. The country's anti-corruption crusade has also taken a substantial hit. Bolsonaro has left a challenging legacy for his successor, Lula da Silva. Peru (-1.16) has likewise languished amid a period of disorganized governance marked by approximately 70 ministerial changes, including seven interior ministers and six defense ministers, in just 16 months.

A novel and, for some, potentially exemplary model of authoritarian governance has emerged under President Bukele in El Salvador. Evading traditional left-vs.-right conflicts, his model opts instead for (seemingly) effective solutions to immediate problems and openly embraces authoritarian tactics. For example, the government employs military force without parliamentary oversight to combat criminal gangs, garnering widespread approval from the public, which appears willing to tolerate human rights abuses in exchange for the substantial reduction in everyday violence.

Once again, positive developments in governance are hard to find in the region. Apart from Honduras (+0.47), notable improvement is evident only in Colombia (+0.50), though this largely amounts to a modest recovery under President Gustavo Petro from the governance losses experienced under the less consensus-oriented and relatively ineffectual former President Iván Duque. It’s worth noting that Uruguay, Costa Rica and Chile have managed to maintain their relatively high rankings, securing the second, sixth and seventh positions out of 137 countries. In Chile and Costa Rica, however, new governments have taken office, with neither left-leaning President Gabriel Boric in Chile nor right-leaning President Rodrigo Chaves in Costa Rica securing parliamentary majorities. Both administrations face substantial pushback to reform efforts. Established governance structures in each have thus far proved resilient, but particularly in Costa Rica, we see the risk of growing populism, while Chile is in the throes of a political upheaval, the outcome of which is uncertain.

Outlook

Across the region, countries are stumbling from one crisis to the next, and many of these countries still lack a societal consensus on medium- or long-term goals. In Argentina and Bolivia, the politics of zero-sum thinking have become so entrenched that forward-looking reform projects are not feasible unless moderate factions on both sides can find common ground. In Brazil, Lula da Silva is facing the shambles left behind by the Bolsonaro era. The extent to which he can disentangle himself from this “friend-enemy” dynamic and offer credible cross-cutting solutions will be pivotal for depolarizing Brazil. Ecuador stands on the cusp of another period of instability, further strained by feeble representational structures. It is entirely possible that we will see the country face problems similar to those witnessed in Peru during the review period.

Much of what comes next hinges on whether and how the region’s countries can extricate themselves from the “negative stagnation” they are experiencing in economic development, a factor that profoundly influences public sentiment and overall receptivity to democracy. In general, growth models characterized by passive integration into the global market, lower productivity levels and extensive informal sectors have reached their limits. When it comes to combating inequality and curbing the informal sector, investments in and reforms of the education and health care systems are as crucial as institutional reforms. However, as things stand, it appears that the status quo will persist for the foreseeable future.